How have we got from the gentleman detective to one whom it is often difficult to tell apart from his quarry? And why, when the likes of Edmund Wilson damned the fiction he inhabits as “no better than newspaper strips” does the detective – cop, private eye or enthusiastic amateur – remain so popular?

It all began with Holmes, of course…

Once A Study in Scarlet had been published, in 1887, the game was well and truly afoot. Though Poe’s Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841) can claim the first detective in fiction, and Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone (1868) is regarded as the first modern detective novel, Conan Doyle’s creation captured the popular imagination to an extent that Poe’s Auguste Dupin and Collins’ Sergeant Cuff had never approached.

The adventures of the Great Detective gripped readers to the extent that, when he was killed off, many took to wearing black armbands. Doyle had known what he was doing from the beginning, of course. He wrote later how it had struck him that “a single character running through a series [in a magazine], if it only engaged the attention of the reader, would bind that reader to that particular magazine”. Readers were bound hand and foot. In their droves…

Holmes was the first successful series detective because he embodied values that readers of the time found convincing. He stood, above all, for science (an exciting new force) and using only the power of his own mind – “like a racing engine tearing itself to pieces” – to fight crime. But Doyle balanced this by making Holmes arrogant, impatient and eccentric. He made him an individual, and in doing so gave him everything necessary to create a very human hero.

Before the First World War, the short story was detective fiction’s predominant literary form. Another successful practitioner was GK Chesterton, whose Father Brown appeared in 1911. Chesterton had strong feelings about the way crime fighters should operate, and his beliefs were at one time enshrined in the oath sworn on joining the British Detection Club. Members had to vow that their fictional sleuths would not be reliant on “divine revelation, feminine intuition, mumbo-jumbo, jiggery-pokery, coincidence or Act of God”.

There was a good deal of rule-making along such lines. In 1929, RA Knox constructed a set of commandments for crime writers, known as the Decalogue, which insist, among other things, that the detective cannot withhold clues from the reader and must not himself be the killer. The Decalogue also instructs that stories shall feature no more than one secret passage and contain no Chinamen, so it has perhaps not dated awfully well, but as a rubric it informed much of detective fiction’s golden age.

Between the wars, the novel displaced the short story. The shifting patterns of domestic life gave women more time to read and to write them, and the period came to be dominated in this country by the so-called Queens of Crime – Agatha Christie, Dorothy L Sayers and Margery Allingham – and their creations Hercule Poirot and Jane Marple, Lord Peter Wimsey and Albert Campion respectively.

Those who damn these writers regard their novels as reflecting a conservative, often fairy-tale, world view in which the do-badder was usually from the lower classes or – worse – a dirty foreigner. It was a world preserved in aspic, far removed from mass unemployment, general strikes, the Great Depression and the rise of fascism. Others, more sympathetic to what became known as “cosies”, insist that the novels grew out of a need for post-war convalescence and healing; readers no longer needed flesh-and-blood heroes and had had a bellyful of onstage violence.

For whatever reason, these tales were massively popular and their detectives were quickly pressed to the public bosom. Christie’s Poirot, who first appeared in The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1921), was a twitching bundle of vanity and foible, the brilliance of his brain contrasting sharply with his seeming disregard for the victim – though as far as detective fiction of the era went, he was hardly unique in this respect.

Allingham – perhaps the most unappreciated of the writers of the golden age – would later develop and stretch the genre, most notably with Tiger in the Smoke, but early on, Albert Campion was little more than a Woosterish, silly-ass figure. Sayers’ Wimsey (which I’ve always thought sounded like a nasty ailment, as in I shan’t stand up, I’ve got a touch of Sayer’s Wimsey

) was perhaps the silliest of them all. With a servant for a sidekick he was, like Campion, and Ngaio Marsh’s Roderick Alleyn, an aristocrat who, like most detectives from this period, has not dated well. These characters, in what Graham Greene described as “stories of forged wills, disinheritance, avaricious heirs and of course railway timetables”, now seem foolish and superior. In the Twenties and Thirties they were pre-eminent, but across the Atlantic a very different kind of detective began to take on cases.

In 1923, Dashiell Hammett wrote a story called Arson Plus for Black Mask magazine, introducing a ruthless investigator known only as the Continental Op. The Op had his own way of doing things, and Hammett had a unique way of describing them. These were the rules of detection as taught to Hammett during his own career working for the famous Pinkerton agency. The detective’s role was to remain anonymous, protect good people from bad, and keep an emotional distance. Hammett published The Maltese Falcon in 1930, distilling all this experience and his own radical world-view into the creation of Sam Spade.

The hardboiled gumshoe was an instant success. Dorothy Parker wrote how Spade had her “mooning around in a daze of love such as I had not known for any character in literature since I encountered Sir Launcelot”. It’s hard to imagine Parker quite so twittery and lovestruck over Englishmen in boaters or egg-headed, mustachioed Belgians.

America did have its own golden age: in 1925, Earl Derr Biggers created Charlie Chan and he was quickly followed by Philo Vance, SS Van Dine’s priggish gentleman sleuth. These cosy characters set the stage for the hugely popular Ellery Queen and, later, Nero Wolfe, Rex Stout’s obese and taciturn sleuth, who was America’s answer to Sherlock Holmes. Loved as all these figures were, however, there were new voices, eager to follow Hammett’s lead and write about characters who operated in the real world rather than the one Raymond Chandler described as “stilted and artificial to the point of burlesque”.

Chandler famously said that Hammett had given murder “back to the people that commit it for reasons” – and it was Chandler who took the hardboiled detective to another level. He defined this new hero as a man “neither tarnished nor afraid”, a man who could walk down mean streets, “though not himself mean” but rather a man of honour and integrity.

Philip Marlowe appeared in Chandler’s The Big Sleep in 1939, and it is no coincidence that his name echoes that of the man who wrote Le Morte d’Arthur. Indeed, in early drafts Marlowe had been called Malory. Like many before and since, Chandler saw the detective as embodying the medieval conception of chivalry. A number of detectives, within their respective milieux, still behave as modern-day knights, Quixotic or otherwise, though the steeds are motorised and the maidens tend to be drop-dead gorgeous redheads. John D MacDonald described his detective Travis McGee as a “tattered knight on a spavined steed,” while even the likes of Peter Wimsey and his blue-blooded cohorts have been called “knights in fancy dress”.

The character of the detective, especially of the private eye for hire, had changed for ever. These were men who worked in a “world gone wrong” and answered to no higher power; not to God, like Father Brown, and certainly not to science, like Holmes or Wolfe. They saw the world from the perspective of the man on the street, and the man on the street couldn’t get enough of them.

The character of the detective continued to develop in contrasting directions after the Second World War. Though Christie and Allingham were still going strong, detective fiction as a form was challenged by the espionage novels of Eric Ambler and Graham Greene, by writers such as Patricia Highsmith (whose thrillers contained no detective at all), and by the emerging sub-genre of the police procedural. Suddenly, even when there was a detective on the case, the novels were about a lot more than the detection itself. Depth of character was as important as the hunt for clues. Writers were keen to explore the psychological make-up of the criminal, and “Why?” had become as important as “How?”

Georges Simenon was deep into what would become a series of more than 70 novels featuring Inspector Maigret, who solved crime through intuition and an understanding of human nature. Marlowe, too, was blossoming as a character, his development through Chandler’s later novels launching an era of socially and politically aware sleuths.

While sensitivity was finding its way into the codes of some detectives, others still preferred the more direct approach. Mike Hammer, introduced in Mickey Spillane’s I, the Jury, had thrown sex and violence into the mix and spawned a host of imitators, with ersatz pulp-fiction from pseudonymous writers such as Darcy Glinto and Hank Janson proving immensely popular in Britain. Hammer and his ilk dealt out their own brand of eye-for-an-eye justice in a series of misogynistic, violent yarns. Others, such as Ross MacDonald’s Lew Archer, continued to explore deeper social issues – and both strains proved to be excellent fodder for film and television.

From its earliest days, the mass media played an important role in the popular perception of the detective. The gentler breed – The Saint, The Falcon, Mr Moto – were hugely popular in the Thirties, but their hardboiled descendants came to define the role during the film noir movement from the Forties on in classic movies such as The Maltese Falcon (1941) and The Big Sleep (1946). Later on, films would introduce the “lone wolf” detective, the anti-authority maverick who shot and drove his way through movies such as Bullitt (1968) and The French Connection and Dirty Harry (both 1971).

The small screen, too, has helped to shape our understanding of the detective, not only with adaptations of novels but with a slew of made-for-TV versions. In the Seventies, American television produced a detective for everyone. It gave us Columbo, who looks like Marlowe and thinks like Poirot, together with a string of “differently abled” detectives: Longstreet, who is blind; Ironside, who is a wheelchair-user; and Frank Cannon, who simply appears to have eaten all the pies. In the UK, the trend was towards ethnicity and regionalism. So we watched Shoestring, the Bristol-based radio detective; Van Der Valk, the Dutch detective; and David Yip as The Chinese Detective, flying solo in the face of one of RA Knox’s sillier commandments…

In the Sixties and Seventies, a new generation of crime queens took the conventions of the golden age and twisted them to their own ends. PD James’s Adam Dalgleish and Ruth Rendell’s Reginald Wexford were from a different background: they were middle-class men, cultured rather than privileged. With Colin Dexter’s opera-loving Inspector Morse, they formed a new wave of cerebral coppers who would become TV favourites and who – while not overly fond of getting their knuckles bruised – were still a million miles away from the top-hatted toffs of half a century before.

In 1972, PD James created Cordelia Gray, one of the first professional private detectives in British fiction. There had been female investigators as far back as the late 19th century, rejoicing in names such as Nora Van Snoop and Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective, but the time was now ripe for women to take centre stage, as opposed to simply being victims, secretaries or pulse-quickening femmes fatales. Writers such as Marcia Muller (Sharon McCone), Sue Grafton (Kinsey Millhone) and Sara Paretsky (VI Warshawski) in the US and Liza Cody (Anna Lee) in the UK, created female private investigators who were every bit as hardboiled as their male counterparts, paving the way for bestselling contemporary writers such as Val McDermid and Patricia Cornwell.

By the late Eighties, a number of important new detectives were appearing in print on both sides of the Atlantic. Ian Rankin’s John Rebus – whose books now account for 10 per cent of all crime fiction sales in the UK – appeared in the same year as Peter Robinson’s Alan Banks. These detectives, together with John Harvey’s Charlie Resnick, are modern men who like a drink and listen to music and have love affairs. They are dour, curmudgeonly even, but essentially compassionate. With Wexford, Dalgleish and Reginald Hill’s double act of Dalziel and Pascoe, they have taken British detective fiction into the 21st century.

In the US, James Lee Burke’s detective Dave Robicheaux (a Louisiana Launcelot), Lawrence Block’s Matt Scudder and Michael Connelly’s Harry Bosch are the pick of a disparate bunch of reformed alcoholics, manic depressives and pill-poppers. Bosch is probably the most rounded, consistently interesting detective in American crime fiction now, his creator ensuring that the character carries the scars of each case to the next book, taking care to re-invent him at regular intervals. Connelly’s Lost Light is one of only two detective novels to make me cry; the other was a classic Christie, but I was crying with laughter at the line: “‘How queer!’ Poirot ejaculated.”

So where does the detective go from here? Mystery fiction has never been more popular, with professionals and amateurs alike busily cracking historical mysteries, forensic mysteries, and – in the United States – cat, cookery, golf and (God help us) quilting mysteries, in their tens of thousands every year.

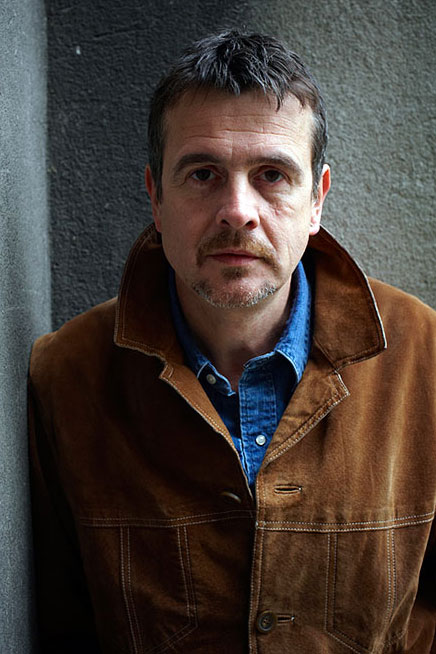

Arguably, the detective in American fiction has not made as great a journey as his or her British counterpart. The spirit of Marlowe is alive in Harry Bosch, and though it’s still too early, it will be interesting to look back in a decade and see just how September 11 might have affected things. In the UK, there are still plenty of fictional flatfoots pounding the mean streets, my own included, though Detective Inspector Tom Thorne – and he is by no means alone – is perhaps a little meaner than Raymond Chandler envisaged 60 years ago.

Some, dismissive of the genre, point to what they see as its clichés: to the battles with the booze and the problems with relationships and the tortured pasts. I’m sure that the majority of real detectives have no more than the occasional half of shandy and live in domestic bliss, and are not haunted by the victims of crimes they could not solve. The evidence would suggest, however, that people do not want to read about these characters, and I for one don’t care to write about them. Who wants to know about a cowboy without a gun or a horse?

Like most of those who write modern detective fiction, I endeavour to make my central character stand out from the pack. I have tried to give Tom Thorne his own insecurities and passions – a blind devotion to a failing football team, a perverse love for country music, an almost total ignorance of when he isn’t wanted and, rather more sadly, when he is.

Above all, I want my hero to be unpredictable. But at the same time, however much he is a character with unique drives and demons, he owes a debt to the detectives created in the past 20 years, as they in turn honour those from a previous era, in the continuing evolution of one of fiction’s most enduring archetypes.

At another point in his latest investigation, Tom Thorne sleeps with someone materially involved in the case, affecting its outcome in a profound and disturbing way. What on earth would the Great Detective have done in the same situation? Well… he’d probably have shut himself away in Baker Street, reached for his violin and his cocaine, and lost himself in an orgy of music and hard drugs.

On second thoughts, perhaps we haven’t come so very far after all.

This article was first written for The Independent in July 2004.

Other Writing

So this serial killer walks into a bar…